After the ring broke, it was time to explain what had happened.

The first photo is two views of the broken ring. The top view is where the pin had been--note the total absence of crazing. Crazing is very evident in the second view, which shows the midpoint between the pin and the girth hitch. An equal amount of crazing is present at the other midpoint, and at least twice as much where the girth hitch had been. These small cracks are very evident to a fingernail, and they indicate where the aluminum was stretching under the tension.

♠

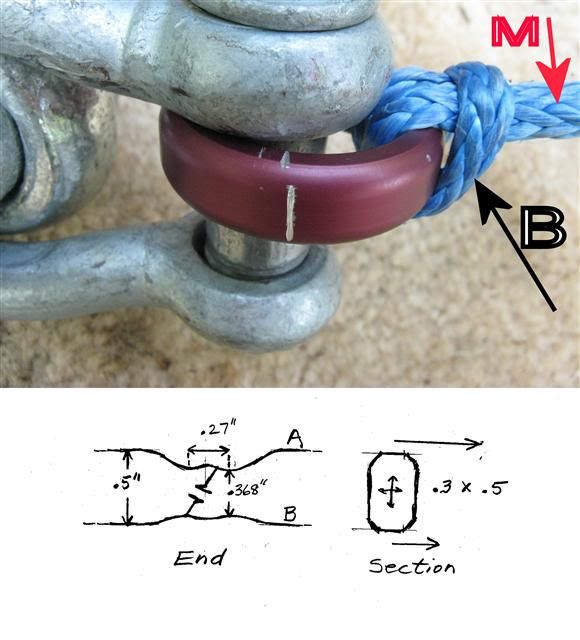

The next photo shows the ring at an early stage of the pull and a drawing showing a reconstruction of the ring just before failure. It is roughly to scale.

To me a convincing description of the ring's failure should explain all the following points:

1.Why no crazing at the pin end?

2.Why the odd pattern of depressions at the girth end?

3.Why the pin end has only a barely perceptible footprint from the pin?

4.Why are the upper depressions at the break about twice as deep as the lower ones?

5.Why did the ring break well below spec?

6.Why has the ring been twisted about 10 degrees at the broken end?

This experiment provoked a good discussion on a different forum, but I can summarize here that the Amsteel Blue sling, far from being a passive and ring-friendly device for pulling the ring, turned out to be the active agent behind the ring's premature failure. The large clevis pin, in contrast, did almost no damage to the ring and even protected the ring from stretch in the contact zone.

All the features at the broken end can be explained in terms of the tremendous crushing force of the girth hitch around almost 300 degrees of circumference and the fact that this force was not symmetrical because the hitch was moving slightly as force increased. The ring was being pulled in two and crushed and twisted in half at the same time.