But they do allow the water to flow from the ground. Dan, let's not be too technical, shall we? Cut all the tree roots off from the trunk, then see what will live upstairs. Ehh?But Dr. Ed.......

....roots don't 'pump' water!

Water Movement in Trees

Kim D. Coder

Professor Silvics/Ecology

Warnell School of Forest Resources

The University of Georgia

http://warnell.forestry.uga.edu/service/library/index.php3?docID=162&docHistory[]=4

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Wood dries from the end? Or sides? Or BOTH?

- Thread starter BlueRidgeMark

- Start date

Help Support Arborist Forum:

This site may earn a commission from merchant affiliate

links, including eBay, Amazon, and others.

Nosmo

Addicted to ArboristSite

Burning a log

One thing about logs or split logs is they will burn on the ends , burn on the sides and burn in the middle.

Nosmo

One thing about logs or split logs is they will burn on the ends , burn on the sides and burn in the middle.

Nosmo

KsWoodsMan

Addicted to ArboristSite

Dan, as already reported by others on this thread, the "death" of a tree does not mean the top alone. The roots continue to feed it water if they are still alive. Even after all of the bark and leaves are all gone, many roots are alive and well beneath the ground, pumping water from the ground into the trunk as best as they can.

It's a pointless effort by the roots, but they do not know any better. So, wood from a "dead' tree can still not be ready to burn in a stove or fireplace, even if split, stacked, and dried in the air for a couple of months.

BULL#### !

Ed, If the roots were still living they would either send up sprouts from the base of the tree or suckers anywhere the roots came close to the top of the soil.

If the tree isn't feeding the roots anymore, they die.

If the roots stop feeding the tree IT DIES TOO.

I have to call bull#### on you again. The bottom 4-6 feet MIGHT have as much moisture in it as a green log. Above that point it is as ready for the fire as it's going to be. That last 4-6 feet of trunk isn't sticky sap so it's goin to turn loose of it's moisture readily. After those 3-4 rounds are cut split and properly stacked it will be more than ready in the time you say it won't.

I just emailed Dr. Coder to see if he can provide me more information.

The article mentions that it is evaporation from the leaves the draws water up the trunk. It may be that evaporation still takes place in dead trees and draws water but I can't find anything on it with a Google search. It's a very interesting subject.

Interested to see what he says Dan.

The local county park cuts rings with a chainsaw around trees in the spring. Then drop and cut up the trees in the winter. They use it for firewood in a house, maintenance shop and warming shelter. Next time I'm out there I'll ask.

OK, thanks for the support, guys. I look forward to someone explaining to me how the inside of a 36" dia. American elm tree that was standing dead for 5 years and no bark left anywhere was wet on most of the inside from 25' high down to the ground this past October. There was no split anywhere in the tree. The branches were dead dry and almost punky, but the trunk was wet. I split and stacked all of it.

How did all that water get there? I am all ears.

How did all that water get there? I am all ears.

Last edited:

palmrose2

ArboristSite Operative

opcorn:

#rd post and I'm LMAO! That popcorn munching is priceless. Obviously you are going to sit back and enjoy the ride.

$215.05

$233.19

Weaver Leather WLC 315 Saddle with 1" Heavy Duty Coated Webbing Leg Straps, Medium, Brown/Red

Amazon.com

$79.99

ZELARMAN Chainsaw Chaps 8-layer Protective Apron Wrap Adjustable Chainsaw Pants/Chap for Loggers Forest Workers Class A

QUALITY GARDEN & HAND TOOLS

$36.99

$59.99

SPEED FORCE Kindling Splitter-Log Splitter-FireWood Splitter–Power Log Splitter Blade Made from CAST Steel, Black Large

SpeedForceUSA

$26.99 ($0.22 / Foot)

$29.99 ($0.25 / Foot)

VEVOR Double Braided Polyester Rope, 1/2 in x 120 ft, 48 Strands, 8000 LBS Breaking Strength Outdoor Rope, Arborist Rigging Rope for Rock Hiking Camping Swing Rappelling Rescue, Orange/Black

Amazon.com

$38.99 ($0.39 / Foot)

Arborist Rope Climbing Rope Swing for Tree(1/2in x 100ft) Logging Rope 48 Strands for Pull, Swing, Knot (Orange)

SDFJKLDI

$337.83

$369.99

WEN Electric Log Splitter, 6.5-Ton Capacity with Portable Stand (56208)

Amazon.com

$14.97

$19.99

Dremel A679-02 Sharpening Attachment Kit, For Sharpening Outdoor Gardening Tools, Chainsaws, and Home DIY Projects,

Amazon.com

$202.29

Oregon Yukon Chainsaw Safety Protective Bib & Braces Trousers - Type A Protection, Dark Grey, Large

Express Shipping ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

$63.99

ZELARMAN Chainsaw Chaps Apron Wrap 8-layer for Men/Women Loggers Forest Workers Protective Chain Saw Pants Adjustable

QUALITY GARDEN & HAND TOOLS

$39.99

$79.99

SPEED FORCE Kindling Splitter Log Splitter FireWood Splitter Power Log Splitter, Long Life CAST Steel Blade, Black (XL)

SpeedForceUSA

palmrose2

ArboristSite Operative

10 to 15 times faster.

I too have said that cutting to length is far and away more important than splitting to drying times.

Let's consider 10 to 15 times faster and cut our pieces into 20" lengths. Let's toss out 15 and say it's ten times faster. That means that a piece of wood will dry 10" from the end and 1 " from the side in the same amount of time under similar conditions. So if you split into 2"x2" slices with no bark, you would essentially half your drying time @ the center of a 20" long piece of wood. That's actually a pretty big deal.

I don't split mine that small. I shoot for around 5"-8" pieces. (I don't want so much surface area in my furnace.) Consequently I don't gain as much as some do by splitting. Keeping the 10 to 1 ratio you can see that if you cut your wood shorter, splitting has less effect. Conversely, If you cut your wood longer, splitting has an even greater effect on dry times.

Differing seat of the pant's observations are directly proportional to how small the wood is split I bet.

I too have said that cutting to length is far and away more important than splitting to drying times.

Let's consider 10 to 15 times faster and cut our pieces into 20" lengths. Let's toss out 15 and say it's ten times faster. That means that a piece of wood will dry 10" from the end and 1 " from the side in the same amount of time under similar conditions. So if you split into 2"x2" slices with no bark, you would essentially half your drying time @ the center of a 20" long piece of wood. That's actually a pretty big deal.

I don't split mine that small. I shoot for around 5"-8" pieces. (I don't want so much surface area in my furnace.) Consequently I don't gain as much as some do by splitting. Keeping the 10 to 1 ratio you can see that if you cut your wood shorter, splitting has less effect. Conversely, If you cut your wood longer, splitting has an even greater effect on dry times.

Differing seat of the pant's observations are directly proportional to how small the wood is split I bet.

I too have said that cutting to length is far and away more important than splitting to drying times.

Let's consider 10 to 15 times faster and cut our pieces into 20" lengths. Let's toss out 15 and say it's ten times faster. That means that a piece of wood will dry 10" from the end and 1 " from the side in the same amount of time under similar conditions. So if you split into 2"x2" slices with no bark, you would essentially half your drying time @ the center of a 20" long piece of wood. That's actually a pretty big deal.

I don't split mine that small. I shoot for around 5"-8" pieces. (I don't want so much surface area in my furnace.) Consequently I don't gain as much as some do by splitting. Keeping the 10 to 1 ratio you can see that if you cut your wood shorter, splitting has less effect. Conversely, If you cut your wood longer, splitting has an even greater effect on dry times.

Differing seat of the pant's observations are directly proportional to how small the wood is split I bet.

This would be true if the capillary drying of the wood was maintained at a fixed rate.It isn't, as the end close quite quickly after being cut.This is how a tree heals itself after pruning, and firewood acts the same way.Leave a round for a year, split it, and you can see the extent of the end drying-about 1/2" or less.

woodbooga

cords of mystic memory

How did all that water get there? I am all ears.

Well it was there to begin with in the form of green moisture content. So I think the better question is "Why ain't it going anywhere?"

To be sure, the ground contains moisture. Whether it's being drawn up by a living root system - or merely by the wood's absorbitant properties seems to be the issue.

Perhaps the guy who did the wood seasoning experiment thread could take up a new project. It would involve 2 bucked pieces of firewood of equal size and weight. One would be an interior split. The other, a bough buck.

Both pieces would be placed in platters containing 1" of water - replenished periodically as absorption and evaporation make the water level drop.

Which ever piece is heavier after a pre-set time period might give us the answer.

Or not. But it's sure a lot of fun arguing about variables in firewood seasoning over the world wide web!

Thanks, WB

WoodBooga is a gentleman, a diplomat, and a scholar who knows how to contribute and not to use X'd-out, 4-letter words when he posts. Such men are rare and valuable.

I reported what I discovered, and I know that it is true what I found.

WoodBooga is a gentleman, a diplomat, and a scholar who knows how to contribute and not to use X'd-out, 4-letter words when he posts. Such men are rare and valuable.

I reported what I discovered, and I know that it is true what I found.

woodbooga

cords of mystic memory

WoodBooga is a gentleman, a diplomat, and a scholar who knows how to contribute and not to use X'd-out, 4-letter words when he posts. Such men are rare and valuable.

I reported what I discovered, and I know that it is true what I found.

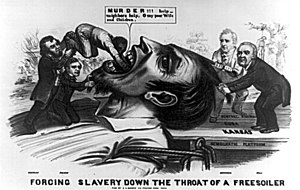

The least I could do. I do, of course, feel some sence of obligation - what with the only President of NH birth signing the law responsible for "Bleeding Kansas."

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kansas%E2%80%93Nebraska_Act

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bleeding_Kansas

Steve NW WI

Unwanted Riff Raff.

OK, thanks for the support, guys. I look forward to someone explaining to me how the inside of a 36" dia. American elm tree that was standing dead for 5 years and no bark left anywhere was wet on most of the inside from 25' high down to the ground this past October. There was no split anywhere in the tree. The branches were dead dry and almost punky, but the trunk was wet. I split and stacked all of it.

How did all that water get there? I am all ears.

My experiences with dead standing elms, albeit much smaller, normally in the 8-14"DBH range, is NORMALLY the opposite, that more than about 8' up the wood is dry, maybe not completely dry, but not green by any means. The lower section will almost always be "wet", but dries quickly when split, showing checking on the ends in just a week or two.

I have had your experience on some trees, though, sometimes right next to a "dry" one, making me wonder if it's just something different in the individual tree's makeup. I'm no scientist, or even an arborist or tree guy, just a firewood cutter relating what I've seen. Make of it what you will.

I did learn from the time I first started helping with wood as a young lad many years ago that split wood dries faster, and smaller splits faster than big ones. This reason, plus ease of handling, is why the majority of my splits are 4-6" on a side, with some larger overnighters mixed in.

KsWoodsMan

Addicted to ArboristSite

OK, thanks for the support, guys. I look forward to someone explaining to me how the inside of a 36" dia. American elm tree that was standing dead for 5 years and no bark left anywhere was wet on most of the inside from 25' high down to the ground this past October. There was no split anywhere in the tree. The branches were dead dry and almost punky, but the trunk was wet. I split and stacked all of it.

How did all that water get there? I am all ears.

Ed, It was there when the tree died . There, that wasn't hard to explain at all.

Our experience may differ but I stand on my original statement when I said bull####. Not just once but twice.

howellhandmade

Addicted to ArboristSite

Hmm, the interesting post with the link to the assertion that wood contains the same moisture midwinter or spring is gone. I've always thought that wood that was cut in the winter took less time to season than wood cut in the spring or summer, but I've never performed the experiment of measuring moisture content of a given species cut at different times of year. The question "where does the water go?" is misleading because water has no trouble going someplace in a tree. When it is in leaf the process is called transpiration (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transpiration). If you consider the trick of letting a felled firewood tree lie until the leaves dry it makes sense that this process could remove a great deal of water from the wood. But in a standing live tree, is it possible that the fact that the sap is moving does not necessarily mean that there is more of it, that the wood tissues retain the same amount of water year round? Some moisture doubtless is lost from the bark, but what would prevent the tree from replacing that moisture? Well, being frozen for one, but perhaps the water being frozen would also prevent it from being lost.

Granted, it's not midwinter, but the leaves have been off the trees here for a few weeks. Three days ago I cut down four or five small, 8-12" maples. I've been splitting them small to dry for kindling, and I was struck by how heavy and wet the logs seemed -- before this thread came up. I realize that it's a commonly held belief that it's best to cut wood "when the sap is down," but I find it interesting that this belief has been challenged. I've always believed it myself, but I'm willing to consider the possibility that it is erroneous to think that because the sap is not actively moving that it is not present. Does anyone else have any sources to support this or actual data to refute it? Perhaps those with moisture meters would be willing to measure the moisture content of splits felled at different times throughout the year, or perhaps it's already been done.

Who knows, it might actually be most effective in terms of drying to fell when the trees have leaves to pull moisture from the wood. I'm not arguing for either side, I'm simply curious.

Jack

Granted, it's not midwinter, but the leaves have been off the trees here for a few weeks. Three days ago I cut down four or five small, 8-12" maples. I've been splitting them small to dry for kindling, and I was struck by how heavy and wet the logs seemed -- before this thread came up. I realize that it's a commonly held belief that it's best to cut wood "when the sap is down," but I find it interesting that this belief has been challenged. I've always believed it myself, but I'm willing to consider the possibility that it is erroneous to think that because the sap is not actively moving that it is not present. Does anyone else have any sources to support this or actual data to refute it? Perhaps those with moisture meters would be willing to measure the moisture content of splits felled at different times throughout the year, or perhaps it's already been done.

Who knows, it might actually be most effective in terms of drying to fell when the trees have leaves to pull moisture from the wood. I'm not arguing for either side, I'm simply curious.

Jack

palmrose2

ArboristSite Operative

This would be true if the capillary drying of the wood was maintained at a fixed rate.It isn't, as the end close quite quickly after being cut.This is how a tree heals itself after pruning, and firewood acts the same way.Leave a round for a year, split it, and you can see the extent of the end drying-about 1/2" or less.

So what you are saying is that my unsplit wood can't cure and I've just never noticed this since 1968? Hmm.

Ever seen the extent of side drying?

I see the extent of side drying every time I burn a piece of well-seasoned wood.I will tell you that buying an EPA stove a few years back taught me what well-seasoned wood is.The stove acts as a lie detector; anything less than dry kills its' performance.Yeah, your small diameter wood will dry unsplit, but your bigger rounds will not dry anywhere near as completely as they would split.

gwiley

Addicted to ArboristSite

standing dead pine dries nicely

Over the past few weeks I have been helping my brother-in-law by removing standing dead pines, most are 70-100' tall with a DBH of 8-15", still standing but are obviously dead as they have lost most of the needles and noticeable portions of the bark.

Before felling I take a whack with the hatchet to judge the degree of punk, too soft means they get felled away from the driveway into the woods, sufficient "hardness" means I drop them next to the driveway for easy bucking and loading. This hatchet test is at 5' and is a great indicator of what the rest of the tree will be like.

The majority of the wood in these pines is dry enough by sight/feel/weight to make me happy to burn them immediately. There is absolutely no question that these trees are seasoned while standing dead.

I HAVE found that within the first 5-10' there is visible water in the wood when I split it - the maul squishes water out when I strike the round (if it doesn't split on the first blow).

These pines appear to grow punky from the bottom up - I attribute this to contact with the ground and from this (and other observations) I conclude (NEWS FLASH......) that dead wood absorbs water. The base of a tree and its roots are in constant contact with the ground - shouldn't be any surprise that they absorb water.

From my observations I conclude:

The wood higher up in the dead tree is sufficiently far from the water in the ground and sufficiently well exposed to wind/sun that it seasons properly while wood in contact with the ground (regardless of whether there are roots) will season less well.

Over the past few weeks I have been helping my brother-in-law by removing standing dead pines, most are 70-100' tall with a DBH of 8-15", still standing but are obviously dead as they have lost most of the needles and noticeable portions of the bark.

Before felling I take a whack with the hatchet to judge the degree of punk, too soft means they get felled away from the driveway into the woods, sufficient "hardness" means I drop them next to the driveway for easy bucking and loading. This hatchet test is at 5' and is a great indicator of what the rest of the tree will be like.

The majority of the wood in these pines is dry enough by sight/feel/weight to make me happy to burn them immediately. There is absolutely no question that these trees are seasoned while standing dead.

I HAVE found that within the first 5-10' there is visible water in the wood when I split it - the maul squishes water out when I strike the round (if it doesn't split on the first blow).

These pines appear to grow punky from the bottom up - I attribute this to contact with the ground and from this (and other observations) I conclude (NEWS FLASH......) that dead wood absorbs water. The base of a tree and its roots are in constant contact with the ground - shouldn't be any surprise that they absorb water.

From my observations I conclude:

The wood higher up in the dead tree is sufficiently far from the water in the ground and sufficiently well exposed to wind/sun that it seasons properly while wood in contact with the ground (regardless of whether there are roots) will season less well.

I cut and burn a lot of standing dead trees. For the most part, standing dead will be ready to burn the day it is cut. Toward the bottom of the tree, the wood tends to get wetter, as capillary action still occurs and the bark tends to stay on lower longer. I've found that trees with bark stay wetter for two reasons: bark holds in moisture and as the bark loosens, it lets in water. Trees that are starting to turn punky on the ouside also stay wetter, for obvious reasons.

I can't answer why the dead elm was so wet. Maybe hollow, punky in places, crack in a crotch (hate that). I think alot of the trees I cut are dead longer than 5 years, but I rarely cut a dead elm, mostly chestnut oak and red oak.

One more thought. I never (or very rarely) find carpenter ants high in dead trees, only within the first 5 feet of so of contact with the ground. Seems the ants know where the moisture is.

I can't answer why the dead elm was so wet. Maybe hollow, punky in places, crack in a crotch (hate that). I think alot of the trees I cut are dead longer than 5 years, but I rarely cut a dead elm, mostly chestnut oak and red oak.

One more thought. I never (or very rarely) find carpenter ants high in dead trees, only within the first 5 feet of so of contact with the ground. Seems the ants know where the moisture is.

Coldfront

Addicted to ArboristSite

One thing I have always noticed is when burning wet or green wood, the heated piece of split firewood the water/moisture always drips or sizzle's out of the end grain. I have never seen water drip or sizzle out of the side's on a piece of heated or burning wet/green wood. This leads me to believe that most drying will occur from the end grains.

Last edited:

Mr Black

Mildly Eccentric

Similar threads

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 380

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 685

- Replies

- 11

- Views

- 2K